“An overwhelming body of evidence supports the belief that whether children learn to read, and how easily they learn to read, is largely dependent on the method by which they are taught. Reading programs that deemphasize the connection between letters and speech-sounds that letters represent, nurture faulty reading; then, children who fail in such programs are labeled dyslexic with the assumption they are not able to learn to read.” Dr. Patrick Groff

With such a wide variety of reading programs and methods on the market today, it can be overwhelming to make sense of them all. Which method is actually best? Does teaching a child to read really have to be so complicated? Why do the “rules” vary so much from program to program?

The Phonics Method

I began creating Foundational Phonics after I started teaching my own students and found myself in a predicament. I needed a phonics program that wasn’t overcomplicated and overwhelming or incredibly tedious and boring. I didn’t want to borrow parts and pieces from a variety of programs like my mother had to do. And the little girl I was tutoring had already attempted a number of programs and was struggling with a speech impediment and symptoms of dyslexia. My extensive search did not lead me to the perfect phonics program (which is why I ended up creating my own) but I did learn a lot along the way about the controversial history of reading instruction in America, the importance of using the true phonics method, and why many phonics programs are complicated and overwhelming.

Our country was founded during a golden age of literacy, where education and self-reliance went hand in hand and dedicated parents guided their children’s education either at home or through private tutors or small schools.

Studying the history and works of pioneers in the field led me to understand why traditional phonics cannot be compared to other methods. True traditional phonics (also known as Synthetic Phonics) reveals the underlying order of the great variety of English spelling patterns, one pattern at a time, in a very logical progression. Yes, there are irregularities in the English language because it is rooted in so many other languages. But true phonics brings order to the exceptions by drawing attention to the patterns (which are seen in the majority of English words).

The English language has 26 letters that make 44 unique sounds all together. With phonics, children begin by learning the basic sounds of each letter. It is not necessary for all the letters to be mastered before reading can begin. The first 3 letters introduced in Foundational Phonics are m, a, n. As the child begins blending those sounds together and discovers that they are able to read the word man, it shows that there is purpose to what they are doing and boosts their confidence. After the basic letter sounds are mastered, phonics instruction continues in a very natural progression of blending sounds to form words, to reading sentences, to reading stories while simultaneously gaining speed and confidence. As concepts are introduced from the simple to the more complex, it becomes a natural extension of learning the language. Children who learn to read through phonics have the ability to sound out and decode practically any word they encounter.

Rudolf Flesch, in his book Why Johnny Can’t Read, put it this way: “Now, with the alphabet, all you had to learn was the letters. Each letter stood for a certain sound, and that was that. To write a word – any word – all you had to do was break it down into its sounds and put the corresponding letters on paper… people all over the world – wherever an alphabetic system of writing was used – learned how to read and write by the simple process of memorizing the sound of each letter in the alphabet. When a schoolboy in ancient Rome learned to read, he didn’t learn that the written word mensa meant table, that is, a certain piece of furniture with a flat top and legs. Instead, he began by learning that the letter m stands for the sound you make when you put your lips together, that e means the sound that comes out when you open your mouth halfway, that n is like m but with the lips open and teeth together, that s has a hissing sound, and that a means the sound when opening the mouth wide. Therefore, when he saw the written word mensa for the first time, he could read it right off and learn, with a feeling of happy discovery, that this collection of letters meant a table. Not only that, he could also write the word down from dictation without ever having seen it before. And not only that, he could do this with practically every word in the language.”

The Whole Word Method

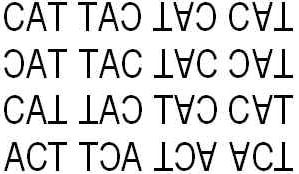

To train a child using the whole word method, the teacher gives the child a picture of a frog with the word “frog” printed underneath, and encourages him to memorize the group of letters that make up the word frog. The child is then asked to practice it again and again with the hope that he will remember what the word frog looks like and what it means. The process must be repeated more or less, for every word the child is to learn, one word after another. Children who are very visually minded can keep up for the short term, but they will never gain the ability to sound-out and learn new words for themselves. Because they are not given the tools they need to accurately decode words, the phonetic framework of our language is made completely inaccessible to them. This in turn reduces “reading” to the equivalent of deciphering hieroglyphics or picture symbols.

With the whole word method, if a child is to be able to read materials with a vocabulary of 10,000 words, then they must memorize 10,000 words; if they want to go to the 20,000-word range, they must learn, one by one, 20,000 words; and so on. Understandably, for children that are not especially visually minded, the whole word method can lead to great confusion and frustration. Words learned in this manner can be easily flipped around in the mind’s eye (was/saw, tea/eat, stop/spot, etc). Studies have shown that the whole word method has actually had a significant effect on the rise of dyslexia.

The History of Reading Instruction

Until I started delving into the history of reading instruction, I hadn’t really understood the significance or importance of true phonics instruction. I was blessed to be homeschooled by my mother. She was born during the time when the whole word method had become the primary teaching method used to teach reading in American public schools and had been for the past 30 years. Just seven years before she was born, Rudolf Flesch published his book Why Johnny Can’t Read, which ignited what were called the reading wars. Many educators and parents, including my grandmother, fought with great effort to bring back phonics to the classrooms. By the time my mother was ready to read she was selected along with a handful of other students to participate in an “experimental” phonics class in her small school in Pelham, New York. Had she never learned phonics, I may have never really learned to read myself and may never have followed the path that led me to write Foundational Phonics.

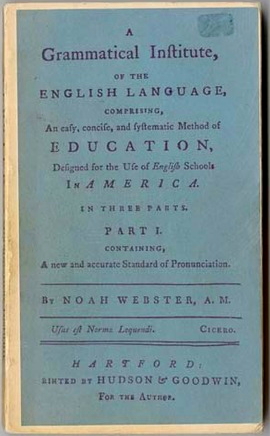

In the 1800’s, shortly after the American War of Independence, a former soldier, Noah Webster, published his soon-to-be famous series, A Grammatical Institute of the English Language – the first book of the series also known as the Blue Back Speller. Webster wanted to extend the ideals of the War of Independence into the realms of language and literature. This series transformed and standardized the way Americans spoke and wrote the English language. It provided teachers with a standard method for teaching spelling. With formal spelling instruction came formal phonics instruction. Among the many teachers who published works during that time, Florence Akin was one of my favorites. She published Word Mastery in 1913, introducing the concept of ear, eye and tongue (multi-sensory) training. She shared her work specifically as a helpful resource for fellow teachers to provide them with a simple framework with which to guide their students through the fine art of reading.

Disputes about the two methods of teaching reading began in 1843 after Horace Mann, the founder of American public schools, traveled to Prussia (now Germany) to study their socialized model of education which he would later help implement back in his home state of Massachusetts (and beyond). While in Prussia, he visited a classroom that made a lasting impression on him. In contrast to the schools in Boston, which sometimes had strict schoolmasters who treated their students harshly, Mann observed children being taught with kindness and respect. He was especially drawn to their seemingly easy method of teaching reading. Rather than harsh drills of letters and their sounds, children were shown pictures with words underneath and were taught to memorize words as a whole without any decoding. Not being a teacher himself, one could argue that perhaps Mann misunderstood the harsh disciplinarian style of certain Boston teachers as one and the same with the teaching of phonics. And in the same way, he misunderstood the kindness of that Prussian teacher as one and the same with learning words as a whole.

Whatever the reason, Mann came back to America condemning phonics, claiming that the alphabetic method (phonics) was “repulsive and soul-deadening to children.” He argued that “children would find it far more interesting and pleasurable to memorize words and read short sentences and stories without having to bother to learn the names of the letters.” He championed the “progressive” idea of replacing all phonics instruction with the whole-word method and was eventually successful in the American public school system.

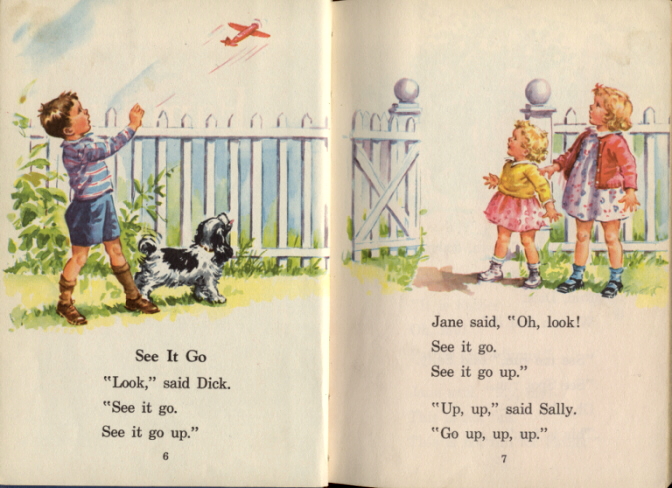

Whole word reading caught on quickly and spread like wildfire. 1846, J. Russel Webb published the first American whole word reader titled, The New Word Method. As whole word advocates argued that phonics was “too irregular, too tedious, too hard,” phonics publishers adapted to keep up with the new trends. Many would be surprised to know that even McGuffy’s readers were written to be taught using either what McGuffy called the “phonic method” or “word method”. Other works that were written to accommodate whole word reading were Dick and Jane Readers by William S. Gray and The Cat in the Hat by Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss).

Sadly, as private schools closed and public education became compulsory across the United States, the teaching of the alphabetic method became scarce. Reading, as we know, it could have been all but lost had it not been for pioneers in the field like Florence Akin, Anna Gillingham, Rudolf Flesch, Jeanne Chall, Samuel Blumenfeld and others who fought with great effort to preserve the blueprint of phonics instruction.

Since the reading wars began, countless studies have been done on the effects of phonics versus whole word instruction. An overwhelming body of evidence has shown that children who learn phonics dramatically excel above children who have not, and that is the only reliable way to ensure literacy.

Even now, though many states have required phonics instruction to be brought back into the public schools, most classrooms do not teach traditional, systematic phonics. The majority of elementary school teachers today have never been taught traditional phonics. With the large, highly structured classroom settings of modern America, individual child-focused phonics training would be quite challenging for most teachers to accomplish. It’s much easier for them to use what they call the “balanced approach,” which is basically the whole word method, with a small amount of phonetic concepts haphazardly mixed in. For instance, the children might be taught to memorize word lists that include words like BEACH and TEACH. If they want to read a sentence with the word PEACH in it, the teacher must draw their attention to the beginning sound of the word and tell them to swap out the B or T and try to replace it with the P sound. With the Balanced Approach, children do not learn to decode or sound out words phonetically, but must base their guesses on picture clues and surrounding context, since they must still memorize the majority of words and word parts as wholes.

The sad reality we now face is that American students have entered an age of functional illiteracy. According to a study conducted by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institute of Literacy, 32 million adults in the U.S. (1 out of 8) cannot read, 21% of adults in the US (1 out of 5) read below a 5th grade reading level, and 19 percent of graduating high school students (1 out of 5) cannot read. The decline in literacy, as well as the rise in dyslexia and other reading disabilities, have been directly linked to the advent of the whole word approach and the phasing out of the traditional phonics model. Yet still, many sectors of the educational system still hold fast to the balanced approach.

Finding the Best Phonics Program

That brings us back to the question, why are so many phonics programs so complicated? There are countless phonics-based programs on the market, but few traditional phonics programs. It seems in an effort to standardize and fit better into the expected highly scheduled classroom model, many programs have simply lost the logical framework of traditional phonics.

Some have separated the parts from the process by isolating word parts and sound combinations to be analyzed and memorized at length before real reading can begin. Others have applied complicated rules to every exception. Still others present concepts in a disorganized order without a systematic logical framework. Another program might have a traditional phonics framework but without any interesting stories or pictures to motivate learning. Many programs use a combination of all the above.

To make up for these complicated approaches, many programs include scripted teacher instructions, and some require intensive multi-year levels to get a child to the point of basic reading.

Any phonics program can get a child farther along than the whole word approach, but not every phonics program is presented in a way that is accessible to every child. If the logical simplicity and order of traditional phonics is missing, the child will inevitably face needless confusion and frustration along the way.

Learning to read is one of the first and most important subjects a child will learn. If they are able to read well, they can teach themselves almost anything. A child’s experience while learning to read can have a pivotal impact on their desire to learn for the rest of their lives. If reading is tedious and frustrating for them, every other subject may seem like a daunting chore to them also. But if reading inspires a love for learning, it can set them up for a lifetime of success.

My goal in writing Foundational Phonics was to restore the beauty and simplicity of traditional phonics and put the power of reading instruction back in the hands of parents. I believe if a child is expected to understand a concept, it should be easy enough for a mother to grasp as well. Complex scripted teacher lessons are not necessary because phonics doesn’t have to be complicated. My sincere hope is that Foundational Phonics will be a blessing to you and your children and that it will be the spark that ignites a wonderful bonding experience and a love for learning in student and teacher alike.